Kelts, of course, are still around today, known as Irishmen, Scots,

Welshmen, and others. The descendants of the ancient Phoenicians are

also around, and are today called Palestinians.

Kelts, of course, are still around today, known as Irishmen, Scots,

Welshmen, and others. The descendants of the ancient Phoenicians are

also around, and are today called Palestinians.

For generations, farmers and explorers have been finding what they assumed were random incisions on stones throughout the Northeast United States. Very little was thought of the odd rocks until archeologist and language specialist Barry Fell, the man singularly responsible for bringing the importance of these scratches to national attention in his monumental work America, B.C., recognized they were ancient writings and actually deciphered one of these inscriptions in 1967.

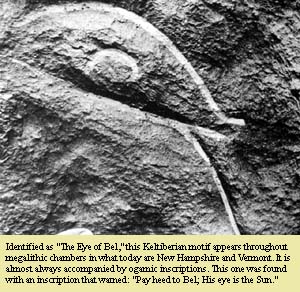

This stone, found at what has come to be known as the Mystery Hill megalithic complex, bore an inscription in what Fell determined was the vowelless style of Keltic Iberian ogam. Much to Fell’s astonishment, the writing turned out to be a temple dedication to the Phoenician Sun god Baal. Another nearby Keltic ogam inscription was deciphered as reading “Dedicated to Bel,” Bel being the Keltic god of the Sun and one and the same with the Phoenician god Baal. The ogam-inscribed flagstone was found near an underground stone chamber aligned to the sunrise of May 1—the sacred day of Bel.

Kelts, of course, are still around today, known as Irishmen, Scots,

Welshmen, and others. The descendants of the ancient Phoenicians are

also around, and are today called Palestinians.

Kelts, of course, are still around today, known as Irishmen, Scots,

Welshmen, and others. The descendants of the ancient Phoenicians are

also around, and are today called Palestinians.

Keltic Sun-wheel motifs, associated with ancient solar observatories throughout Europe, were also found at the Mystery Hill site and other megalithic sites in New England.

Further, Fell and others have found “eye of Bel” engravings on glacial erratics and inside solar chambers across northern New England that are clearly related to European examples of the same motif.

After this epigraphic breakthrough, information began pouring in. People now were convinced the incised rocks they had found on their properties were more than they had been told by skeptical “experts” for years. In fact, hundreds of ogamic inscriptions were found side by side with Phoenician inscriptions. Many of the ogam-inscribed flagstones interested people brought to Fell were found to have been grave markers, the location of the grave sites now lost due to their removal, unfortunately.

However, it seemed clear to Fell and his associates that the Kelts of the Iberian peninsula and the British Isles must have been the builders of the Mystery Hill site, judging from the similarity of the megalithic structures found there and those in Spain, Brittany, Portugal and Britain and also because it was these same Kelts who had lived side by side with the Phoenicians in ancient Iberian seafaring settlements, exchanging writing styles and languages. Further, the linguistic idiosyncrasies found beside the Keltic inscriptions at Mystery Hill appeared to be unique to a Punic style used in the period from 800 to 500 B.C.

Recent ogamic tract finds are not confined to New England. Gene Ballinger, writing and researching for the Courier newspaper of New Mexico, has stated that he has found and identified hundreds of Keltic ogam inscriptions in the rocks of the Southwest including: Keltic war god petroglyphs; mother goddess Byanu petroglyphs and petroglyphs of a Keltic water goddess. In each of the instances where the Keltic water goddess symbol was found, previously unknown, ancient hand-dug and rock-lined wells were found. Ballinger has also located many more ogamic inscriptions—one a deeply incised, five-foot tract in the boulders of southwestern New Mexico.1

Gloria Farley, an ardent archeologist and explorer, has found countless examples of what seem to be Keltic ogamic inscriptions along the Cimarron River in Arkansas and more in Kentucky, leading her to believe Kelts were exploring the Mississippi River valley and leaving their inscriptions along the way 1,000 years and more ago.

Now is it possible the inscriptions Fell and others have discovered are not European ogam at all, but a similar style of writing that may have developed independently in America? Fell, considered the world’s foremost expert on rock alphabet engravings before his death in 1994, claimed the odds against the American Indians developing a 12-character ogamic scriptural writing style just like its Bronze Age Iberian counterpart were about 430 million to one.2 And the chance the 17-letter ogamic alphabet found on the rocks at Monhegan, Maine was Amerindian is even more remote.

It is therefore not improbable the ancient ogamic inscriptions found on the rocks in New England were written by Iberian and Goidelic Kelts and Iberian Phoenicians. But could they have been clever forgeries?

In response to this possibility, Fell and his associates photographed any new find, and the photos clearly show the team removing hundreds of years of lichen and other plant growth from rocks they supposed might have inscriptions. If they are forgeries, they were done by someone many decades before the present, with incredible language skills, enthusiasm and knowledge of the art of the vowelless ogamic scriptural style which was lost sometime around 200 B.C. (The vowelled style took over about then.) Under the circumstances, this possibility seems remote.

And if epigrapher Barry Fell and James Whitehall of the Early

Sites Research Society have accurately read several stone inscriptions

they found in New England, there is additional evidence the Phoenicians

were in America 2,500 years ago and trading with a thriving Keltic

community here.

And if epigrapher Barry Fell and James Whitehall of the Early

Sites Research Society have accurately read several stone inscriptions

they found in New England, there is additional evidence the Phoenicians

were in America 2,500 years ago and trading with a thriving Keltic

community here.

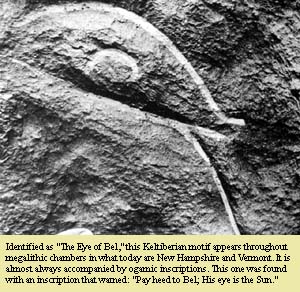

Several miles off the coast of Maine, near Monhegan Island and more precisely on a small, flat-topped island called Manana, Fell found an inscription in Goidelic Keltic—the Bronze Age predecessor to Irish—which has been deciphered as saying: “Ships from Phoenicia: Cargo Platform,” the Manana Island site being suitable for lading trade goods.

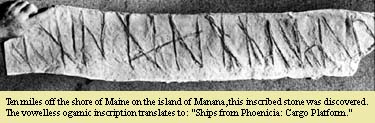

Further evidence of the Phoenician and Keltic willingness to brave the open seas was found in 1975. In the spring of that year a stone measuring 45 inches by 15 inches tall was deciphered by Fell and Whitehall as reading, “A proclamation of annexation. Do not deface. By this Hanno takes possession.” The stone had been discovered by colonial settlers in 1658 and was being used as a doorstop when someone realized its possible antiquity and brought it to Fell’s attention.

We do know there was a real historical figure named Hanno—a Phoenician seafarer who explored and colonized along the African coast around 500 B.C., founding seven cities and setting up several trading posts. The Greeks had copied inscriptions from the Temple of Baal in Carthage, and they survived in manuscript form from the 10th century A.D. referring to the voyages of this man. Hanno was said by the ancient Greeks to have circumnavigated the Atlantic (referred to as “the northern ocean”) sometime around 480 B.C. But their accounts also tell us Hanno was a king of southern Spain, with his home port being Phoenician Cadiz. The New England inscription was written in the style of southern Iberian Punic, and the Phoenicians were the founders of the city of Cadiz. It is interesting to note, the Phoenicians’ documented travels from Iberia to Africa and then to India would have been twice as long as an Atlantic crossing.

But did the inhabitants of Bronze Age Iberia actually possess the capability to travel from the Old World to the New World, and what do their contemporaries say of them?

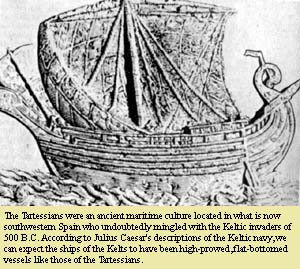

Around 1110 B.C., it is accepted by all historians, the Phoenicians were active throughout the Iberian region, settling the southern areas of Spain and mingling with an older, established civilization called the Tartessians. Not much is known about the Tartessians other than that they were an adventurous maritime people. They are mentioned at least 28 times in the Old Testament. Apparently their culture was centered in what today would be southwest Andalusia.3

As a sea and trading power the Phoenicians (known to the Greeks

as the Phoenekoi—“wearers of the blood-red [purple] cloth”)

made alliances easily. They were well known as the builders of some

of the largest seagoing vessels of the period and the most active explorers

of the Bronze Age. We hear of their sailing prowess in several of the

Biblical Psalms. By 700 B.C. the Phoenicians had become the leading

suppliers of raw materials to the Assyrian empire and were agents of

both the Egyptians and the Assyrians. They were relied upon to provide

gold, tin, copper and other precious goods to these great powers.

As a sea and trading power the Phoenicians (known to the Greeks

as the Phoenekoi—“wearers of the blood-red [purple] cloth”)

made alliances easily. They were well known as the builders of some

of the largest seagoing vessels of the period and the most active explorers

of the Bronze Age. We hear of their sailing prowess in several of the

Biblical Psalms. By 700 B.C. the Phoenicians had become the leading

suppliers of raw materials to the Assyrian empire and were agents of

both the Egyptians and the Assyrians. They were relied upon to provide

gold, tin, copper and other precious goods to these great powers.

However, complete disaster befell the Carthaginian/Phoenician empire. The Punic Wars pitted the Carthaginians against the Greeks and Romans. These wars were waged during the three centuries before Christ. The first Punic War took place between 264 and 241 B.C. and ended in victory for the Romans, who annexed Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia from the vanquished.

The Carthaginians, however, under Hamilcar Barca, went on to conquer most of Spain (236-228). And Barca’s work was continued by his son-in-law Hasdrupal and Barca’s famous son Hannibal. By doing so, as historian W. David Crockett points out, the Carthaginians gained control of the Tartessian mines and were able to hire Keltic recruits for their army. Carthage lost Spain in the Second Punic War (218 to 210 B.C.), and the entire Carthaginian culture seems to have been destroyed in the Third Punic War (149 to 146 B.C.) with the destruction of Carthage itself in 146 B.C.

The Romans then took power over the Phoenicians, outlawing their religious rituals, including human sacrifice. After the fall of Carthage, the Mediterranean was completely closed to Phoenician traders, and historian Robert Ellis Cahill tells us they sailed away from North Africa in great numbers, never to be seen again.

Were they in search of economic, political and religious freedom? Could they possibly have sailed to the Americas to avoid persecution and tyranny?

Aristotle, in his Marvels of the World, written in 335 B.C., revealed that “outside the Pillars of Hercules [Straits of Gibraltar], the Carthaginians have found an island having woods of all kinds with remarkable fruits and navigable rivers.” This may have been a reference to the Americas. (Ancient mariners called any newly discovered piece of land an island, as they had no way of knowing, without attempting to sail around it, whether it was an island, a peninsula, or a continent.)

Well before this time, bands of Kelts, long known as great warriors, explorers and craftsmen, had invaded the Iberian peninsula, from central Europe. Keltic advances into southern Iberia (a Phoenician sphere of influence) were relentless, and the Phoenicians of Iberia finally succumbed to their invasions sometime around 500 B.C. The Phoenicians were eventually absorbed by the settlers—the regional written language changing to Keltic around then. But as with many conquerors, the cultural traits of the victor mingled with those of the conquered. The Kelts learned to speak the Phoenician language, probably for ease of trade, and adopted many of the Phoenicians’ maritime and commercial traits as well. Huge numbers of Keltic mercenaries marched with Hannibal across the Alps to ravage the Roman armies for almost a decade during the Second Punic War.

But the Kelts were also known as great seamen by their peers. Julius Caesar gives us one of the few reliable historical accounts of a Keltic navy in his De Bello Gallico, Book III, which deals exclusively with his impressions of a naval battle fought off the shores of Brittany (Armorica) in A.D. 55. His adversaries were the ferocious clans of mainland Europe who called to their aid their brethren, the Kelts of the British Isles. Caesar, a meticulous historian, tells us the Kelts were able to muster a force of 220 ships, all of which were bigger and more sturdily constructed, better sailed and steered than his own impressive navy’s ships.4 He described the Keltic ships as massive, high-prowed, flat bottomed and keeled.

Their sails were leathern—not the relatively flimsy cloth

of Roman and Egyptian craft. Caesar adds that the rigging was of braided

leather and that their helmsmen were able to tack, to sail against

the wind. Further, the wooden planks of their vessels were bound in

iron, not rope like less sophisticated vessels of the period, and their

anchors were of iron, not the stone anchors his galleys were still

using.

Their sails were leathern—not the relatively flimsy cloth

of Roman and Egyptian craft. Caesar adds that the rigging was of braided

leather and that their helmsmen were able to tack, to sail against

the wind. Further, the wooden planks of their vessels were bound in

iron, not rope like less sophisticated vessels of the period, and their

anchors were of iron, not the stone anchors his galleys were still

using.

It was the Kelts who were the preeminent ironworkers of this age, fueling the Halstatt and La Téne Iron Age cultures. In fact the Kelts are given credit for some of the greatest iron inventions in European history: the horseshoe; the hand saw; the plowshare; the rotary flour mill; a wheeled harvester and chisels, files and other hand tools, the design of which has changed little since their Keltic origins.5

All in all, Caesar was quite impressed with the sturdy and graceful nature of the enemy ships and in fact surprised by Keltic seamanship and ship construction. And we can further surmise Keltic shipbuilding and sailing techniques weren’t devised overnight—they were the product of centuries of accumulated knowledge. It is enlightening to compare the Keltic navy’s massing of 220 ships which could each carry 200 warriors and were 120 or more feet long to the three puny, leaky ships (two of which were around 50 feet in length) and the 88 men Columbus could muster for his transatlantic voyage 1,400 years later. What hubris to believe these people lacked the ability to sail to the New World millennia before Columbus.

And knowing of the keen knowledge the Keltic intellectuals possessed of the lunar phases, their ability to predict eclipses, their familiarity with the precession of the constellations, and their vast storehouse of astronomical knowledge, gleaned from sites like Stonehenge, Fell quite confidently states that Keltic mariners would have been able to sail by the stars and the Sun across great distances, across the Atlantic, at the right time of year, to “the land beyond the sunset.”

As traders and explorers the Phoenicians and Kelts were continually looking for new markets. One Phoenician merchant of the Bronze Age has been quoted as saying, “A virgin market is ideal since it can be scoured hard for huge profits.”6 And they were always looking for new trading partners and new suppliers of exotic trade goods and raw materials. The copper fields of the upper Michigan region were certainly one untapped source of pure copper and other metals that could have been mined and shipped back to metals-hungry Europe and sold for a great profit. And the archeological evidence of the region supports this thesis.

According to author Louis A. Brennan, in his thought-provoking book No Stone Unturned, “float copper” (pure surface copper that need not be smelted) was abundant in the Michigan region and had been mined since 4,000 B.C. by an ambiguous culture known as the Lamokans—one he says was not related to the modern Athabaskan Indian inhabitants of the region. This culture, he speculates, may have come from Europe via an Atlantic land bridge, but there is little evidence to support that theory. But the evidence does support two points: Ancient cultures were mining the float copper found in the Michigan region long before the Bronze Age and there was a strong Caucasoid presence in the area.7

We also find throughout the region scores of vowelless ogamic inscriptions in the Punic and Keltic dialects associated with the copper mines, proving these two groups were there at least as early as the first five to eight centuries B.C. And European travelers may very well account for two cultural mysteries of the area. One is the blond-haired, blue-eyed Mandan Indians, whose origins have puzzled anthropologists for decades. They were most likely the descendants of ancient European metals miners. According to author Gene Ballinger, they spoke a form of ancient Gaelic to such a degree that English explorers of the 15th and 16th century who were familiar with the Gaelic languages of Ireland and Scotland were able to converse with them.

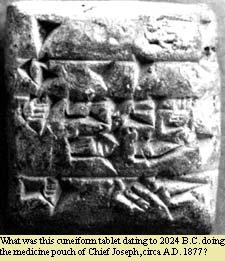

The other is the presence of an enigmatic item found in the medicine

pouch of Nez Perc Chief Joseph upon his capture in 1877. In this hide

bag was found a cuneiform tablet whose inscription dates from 2042

B.C. The tablet was said by the chief to have been an inheritance from

his white ancestors—bringers of great knowledge to his people

eons ago.

The other is the presence of an enigmatic item found in the medicine

pouch of Nez Perc Chief Joseph upon his capture in 1877. In this hide

bag was found a cuneiform tablet whose inscription dates from 2042

B.C. The tablet was said by the chief to have been an inheritance from

his white ancestors—bringers of great knowledge to his people

eons ago.

Another important puzzle piece to this ancient mystery of trade between Phoenicians, Iberian Kelts and Bronze Age Europeans has been brought to light by scuba divers working at a depth of 120 feet in Castine Bay, Maine. Two large ceramic jars were recently hauled to the surface. They have turned out to be ancient olive jars from the Iberian peninsula. The amphorae display clear chafing patterns like those rope lashings would make during a long ocean voyage. More Iberian amphorae have been found in the waters off Newburyport and Boston, Massachusetts.8

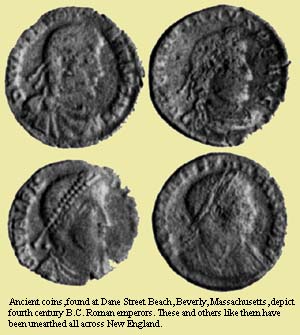

Further, Fell and others have found scores of ancient coins throughout

the New England area. He said, “After the 4th century B.C. our

visitors began to leave behind infallible date markers: those enduring

metal discs called coins.” The coins were inscribed with letters

indicating they were issued to be used as pay for mercenary Greek and

Iberian soldiers in the Carthaginian army.9

Further, Fell and others have found scores of ancient coins throughout

the New England area. He said, “After the 4th century B.C. our

visitors began to leave behind infallible date markers: those enduring

metal discs called coins.” The coins were inscribed with letters

indicating they were issued to be used as pay for mercenary Greek and

Iberian soldiers in the Carthaginian army.9

Ballinger notes that Carthaginian coins have been found in 11 states in 50 separate sites. Some of these coins are today worth thousands of dollars each, making it unlikely they were “dropped” by collectors.

The Phoenicians and the Kelts lived in Iberia together for generations—perhaps as long as 500 years side by side. They were ancient enemies of the Romans, great warriors, tradesmen and seamen. It would seem logical that they would venture together across the Atlantic for economic opportunities and to find freedom from Roman oppression.

Once the Kelts got to the shores of America, they could not have built the sophisticated megalithic complexes found in New England overnight (assuming these were constructed by the Kelts and not some unknown, earlier people). It would have taken them decades to found settlements, repair and build ships and set up the social structures necessary for the undertaking of the building projects we find in the New England area. Newcomers just don’t start building astronomically aligned chambers and setting up stone circles. They first must build houses, grow crops, ward off any hostile natives and establish all the other basics of stable civilization. This doesn’t mean a priestly class wasn’t setting up site stones and smaller monoliths, marking true north and other basic foundations for a future site.

Judging from the number of accurately functioning calendar sites in New England, it must have been a priority of an established settlement to construct one for themselves. But why was it so important?

It would appear the Kelts used the calendar sites in New England to regulate their year, to set planting and harvesting schedules and feel as though they had some loose control over the cycles of nature. We are drawn to this conclusion because the calendar sites clearly break the year into eight equal divisions related to the Sun, with the solstices and equinoxes as the four basic dividers. (The Kelts used both a lunar and a solar calendar. Many other cultures broke their year into 13 months [“moonths,” if you will] based upon the lunar cycle. It is said a solar cycle is more accurate, eliminating the need for leap years and the quarter day we pick up each year from our present calendar.)

The monoliths, solar chambers and accompanying ogamic inscriptions we find in New England always align to sunrise and sunset positions of the most important of Keltic ritual days.

Beltane (“the Fires of Bel”) was the first day in the Keltic calendar (our May 1) and was the holiday dedicated to the great god Bel. It was the Kelts’ most important yearly celebration. Beltane is the modern Irish name for the month of May. We celebrate this holiday as May Day, when children dance around a May pole, stomping the ground. It is a day for dancing and games and sports. Historically, May has been viewed as the month in which winter was finally over and the fruits of spring begin to ripen. At Mystery Hill, and other sites, the largest monolith was the one marking the sunrise of May first, and this day may have been the cue to drive grazing animals to their summer pastures.

Neolithic people probably danced around stone phalli like those

still to be found throughout New England, their May Day festivals taking

on a decided fertility aspect. Many believe our own May pole is a more

palatable version of the ancient stone phalli that were almost completely

eliminated in Christian Europe. Such stones remain standing at many

New England sites, giving us an insight into the religion of the ancient

Europeans. (In India today many Hindus still worship the lingam and

its feminine counterpart the yoni.)

Neolithic people probably danced around stone phalli like those

still to be found throughout New England, their May Day festivals taking

on a decided fertility aspect. Many believe our own May pole is a more

palatable version of the ancient stone phalli that were almost completely

eliminated in Christian Europe. Such stones remain standing at many

New England sites, giving us an insight into the religion of the ancient

Europeans. (In India today many Hindus still worship the lingam and

its feminine counterpart the yoni.)

The next great holidays of the Kelts were Litha (the celebration of the summer solstice), Lammastide (the August first celebration when the first grains of fall are made into loaves of bread) and the fall equinox. At the megalithic complex at Mystery Hill, and others, all these Keltic holidays were marked by sunrises or sunsets over stone monoliths or the entry of the Sun into the small openings in the ceilings of slab-roofed chambers.

After the fall equinox, the next yearly division of eight would occur on November 1. This is when the Kelts celebrated Samhain—the predecessor of our Christian Halloween (October 31). On Samhain, the Kelts believed, the spirits of the dead could walk in the real world and make themselves known to the living. It is symbolically the start of winter and the end of mild weather and was an important druidic holiday marked by bonfires (fires of bone) as flames were thought to welcome friendly spirits and ward off bad ones. Fire pits are a common find near the megalithic structures that align with the sunrise and sunset on this holiday.

On December 21, the Kelts celebrated the winter solstice. This day marked the beginning of lengthening days and the slow march to spring. This holiday too has its sunrise and sunset monoliths as well as solar-aligned underground chambers at our New England megalithic sites, just as one would expect.

Succeeding the winter solstice, we would find a Keltic holiday on or near February 1. This holiday was known as Imbolc and indicated the start of the lambing season. “Imbolc” may mean “sheep’s milk.” And just as we could expect, there is a great monolith at Mystery Hill that aligns to the sunset on this date. An underground solar chamber is also bathed in sunlight on this date every year. Many suspect the American festival of Groundhog Day (Candlemas Day) is a modern-day parallel to Imbolc: Each February 2nd we all look for the shadow cast by the rising Sun upon a standing object (Punxsutawney Phil) to determine the continuation or abeyance of winter.

Further tying the holiday to the Kelts, an old Scottish saw proclaims: “If Candlemas is fair and clear/There’ll be two winters in the year.”

And finally we come full circle on the Keltic year with the celebration of the spring equinox, obviously a holiday with ties to rebirth and regeneration. The Kelts celebrated this day as the triumph of the Sun over the cold grip of winter’s death and dedicated the holiday to the goddess of the dawn, Eostre, the derivation of our Christian word Easter, which we have adopted as a joyous celebration of the rebirth and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the first Sunday following the first full Moon or after the vernal equinox.

Taken together, these holidays, which many of us still celebrate in one form or another today, break the year into a perfect division of eight parts—just as scholars predicted. In short, it is obvious the calendar sites of New England were used to regulate the year, cue planting, harvesting and animal husbandry cycles and could even predict eclipses of the Moon. Holidays and great celebrations would also begin and end according to the dictates of the stone chambers and monoliths, the Sun’s position telling the Keltic priestly class (druids and druidesses) all they needed to know to stun and amaze the populace with their accuracy if they so desired.

The druids must have learned their craft from an existing group of wise men who had carried on the astronomical knowledge from the ancients who had built Stonehenge, and some believe the Keltic druids were no more than students of that ancient, unknown religious/intellectual caste—perhaps the Red Paint people or the Battle Ax people of ancient Europe, and possibly related to the Lamokans.

The druids were the intellectual class of the Kelts during their entire cultural history—from the time of their migrations from the headwaters of the Danube until their entry into the British isles. This author will say, much to the consternation of some readers, that the druids did not have a hand in the building of Stonehenge. That timetable is about two thousand years off.10

No matter, the druids were intelligent philosophers, setting up institutes of higher learning and using the existing megalithic “observatories” to glean vast knowledge about the Moon, stars and Sun. Almost no decisions could be made, sacrifices offered or battles fought, without the presence of a druid priest or druidess.

The leaders of the druidic cult were divided into three basic categories: bards (the sect responsible for preserving literature and music); the vates (those responsible for carrying out sacrifices to the gods); and the druids proper (those responsible for studying natural science, philosophy and astronomy).

The vates, it was said, would augur from the death throes, entrails and spurting blood of a sacrificial victim. It may have been the vates especially who were wiped out by the Romans during their occupation of the British Isles, as the Romans claimed they were disgusted by the human sacrifices practiced by this sect. (This from a people that made mass execution, gladiatorial combat to the death and the feeding of unarmed people to wild beasts a spectator sport.) More likely the Romans (as was their policy of conquest) were attempting to wipe out the intellectual and religious castes of the Keltic peoples and providing the gullible with a good public relations reason to do so.

When the Kelts came to the New World, they were surely accompanied by their learned men—druid astronomer priests. And there is evidence to support this theory.

In September 1941, two boys playing on Great Chebeaugue Island in Casco Bay, Massachusetts began scraping moss from a large boulder facing the sea. To their surprise they discovered a life-size Caucasoid face (closely resembling a druid) carved with great skill. Fishermen who had lived on the island in the 18th century had reported seeing a carved face in the rocks, which they said had been discovered by the first island settlers. No one, however, could ever relocate the stone face until the boys stripped off the layers of moss. Jim Whittall concluded the face was carved by Keltic explorers sometime before A.D. 1000. The artistic style of the carving is obviously similar to that of the Kelts.

Another druid head just like that found at Casco Bay, adorned with oak leaves and acorns, was found in the bedrock at Searsmount, Maine and is presently on display at the Sturbridge Village Museum in Massachusetts. The connection to the oak is significant as the pagan Keltic druids considered the oak to be sacred (an idea which comes from the Indo-Europeans) and used the acorns and the leaves in their religious ceremonies. Some linguists claim the root of the word “druid” means “oak knowledge.”

But if in fact the Kelts were inhabiting what was later to become the homeland of the Algonquian Indians, there must be some cultural memory of this great migration and habitation. And there is.

One reliable Norse account of the voyage of Thorfin Karlsefni in A.D. 1123 claims the Viking explorers came across blond-haired, blue-eyed inhabitants of New England who spoke a form of Gaelic. One account tells that these people lived in underground chambers, like those we find today in New England. Whether these Gaelic speakers were Culdee (i.e., Keltic Christian) monks or pagan descendants of the ancient Keltic inhabitants of the New World is moot.11

And, the Algonquian Indians of the American Northeast clearly display characteristics of the southern European and Mediterranean racial stocks. They, unlike the obviously Mongoloid Athabaskans and Eskimos, have neither the epicanthic “oriental” eye fold, the yellow-hued skin, the “Mongoloid blue spot” pigmentation of the lower back of some Asians that disappears after puberty, the round-headedness, the short nose nor the small stature typically associated with the Mongoloid racial type. Algonquians typically display the aquiline “Roman” nose, obviously different from the Mongoloid nose. When the Algonquian intermarries with a Caucasian, their offspring are said to be more Caucasoid in appearance than if a Caucasian mixes with any other race on Earth. Why? Possibly because the Algonquian racial type is already part European.

There is also an ancient Wampanoag story of a great battle fought between white invaders and their tribe eons ago. The invaders came upstream in a large flat-bottomed ship with a “house” on the back. This may have been a reference to a Phoenician or Keltic vessel, as these peoples often added towers to the backs of their vessels for defensive purposes.12

But even more than these oral remembrances, the Algonquian language

of the New England region convinces us of Old World Keltic contact.

The Algonquian word “Amoskeag” means “one who takes

small fish.” The Keltic “Ammosiasgag” means “small

fish stream.” The Indian “Merrimack” River has been

interpreted in Algonquian as “deep fishing.” But the Keltic

“Morriomack” means “great depth.” The “Piscataqua”

River is said to mean “white stone,” and it bears a striking

resemblance to the Keltic “Pioscatacua” meaning “pieces

of snow white stone.” The Indian “Pontanipo” Pond means

“cold water” pond. The Keltic word for “numbing cold

pool”?—“Punntainepol.”

But even more than these oral remembrances, the Algonquian language

of the New England region convinces us of Old World Keltic contact.

The Algonquian word “Amoskeag” means “one who takes

small fish.” The Keltic “Ammosiasgag” means “small

fish stream.” The Indian “Merrimack” River has been

interpreted in Algonquian as “deep fishing.” But the Keltic

“Morriomack” means “great depth.” The “Piscataqua”

River is said to mean “white stone,” and it bears a striking

resemblance to the Keltic “Pioscatacua” meaning “pieces

of snow white stone.” The Indian “Pontanipo” Pond means

“cold water” pond. The Keltic word for “numbing cold

pool”?—“Punntainepol.”

These are just a mere few of the hundreds of similar Keltic and Algonquian place names that seem to be so close in pronunciation as to go beyond coincidence.13 Even the Vikings noticed the many similar words they found when conversing with the Algonquians.

It is more likely the Algonquian language is still strongly reminiscent of that of the ancient Keltic inhabitants who once roamed the forests of New England, set up the mysterious and sophisticated megaliths still being uncovered there and proudly carved their names in the rock faces boldly proclaiming their amazing accomplishments. And judging from thousands of recent finds of ogamic inscriptions from the Cimarron River basin in Oklahoma, to the Rio Grande in the south, to the mountains of Montana, to the river basins of Colorado, to the Pacific coast of South America, the New World Kelts were far from confined to New England. It appears likely they explored nearly every part of the Western Hemisphere thousands of years before the birth of Christ and up until as recently as A.D. 700.

The origin of the New England megalithic sites is most definitely

Euro-American and not Amerindian. What a shame our children may never

be taught the truth about these incredibly sophisticated early Europeans

and European-Americans whose sites are, to this day, gathering places

for astonished citizens who come to witness the rising or setting of

the summer Sun over huge megalithic boulders set in place with great

effort by these magnificent architects thousands of years ago.

The origin of the New England megalithic sites is most definitely

Euro-American and not Amerindian. What a shame our children may never

be taught the truth about these incredibly sophisticated early Europeans

and European-Americans whose sites are, to this day, gathering places

for astonished citizens who come to witness the rising or setting of

the summer Sun over huge megalithic boulders set in place with great

effort by these magnificent architects thousands of years ago.

Puzzlingly, however, carbon dating and archeo-astronomical data at the Mystery Hill site reveals a probable start date for the construction there as long ago as 2000 to 2500 B.C. This coincides more closely to the culture that built the great megalithic sites found at Stonehenge and Avebury in England and the immense Ring of Brodgar in Scotland (3000 B.C.). Like these cultures, no metal tools were used to carve the great stones of the earliest New England megalithic sites.14

Why wouldn’t the Kelts have used their sophisticated bronze, and later iron, tools to aid in the construction? Is it possible the Kelts merely finished or added to these American sites begun by an even older culture? The implications are enormous and deserve investigation.

Speculation has begun, even among the Establishment, that a Caucasoid race may have inhabited the Americas in a far distant era, possibly wiped out by hostile natives.

More likely, this race intermarried with the Amerindians of the

area after exchanging sophisticated tool-making, agricultural, mining

and pottery-making techniques. Were these the white “ancient ones”

that appear so central in so much ancient Indian lore? Were they the

founders or the impetus for the Anasazi and Hopewellian cultures? Only

time, and further research, will tell.

![]()

7. Louis A. Brennan, No Stone Unturned. (New York, New York: Random House, 1959), p. 89.

10. Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury. (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1979), p. 49.

America, B.C.—Ancient Settlers in the New World, Barry Fell, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1976.

America’s Stonehenge—An Interpretive Guide, Joanne Dondero Lambert, Sunrise Publications, Kingston, New Hampshire, 1996.

America’s Stone Relics—Vermont’s Link to Bronze Age Mariners, Warren Dexter and Donna Martin, Academy Books, Rutland, Vermont 1995.

Ancient and Modern Quarry Techniques, Dr. David Stewart-Smith, Gamesmasters Publishing Association, Nashua, New Hampshire, 1989.

Archaeological Anomalies, W. David Crockett, Anundsen Publishing Co., Decorah, Iowa, 1994.

Courier, The, Volume 19, No. 35, Gene Ballinger, Rio Valley Publishing Co., Hatch, New Mexico, 1995.

Celtic Connection, Michel-Gerald Boutet, Gloria Farley and Others, Stonehenge Viewpoint, Santa Barbara, California, 1990.

Celtic Secrets, Donald L. Cyr, Stonehenge Viewpoint, Santa Barbara, California, 1990.

Celts, The, Merle Severy, National Geographic, Volume 151, No. 5, May 1977.

Native American Myths and Mysteries, Vincent H. Gaddis, Borderland Sciences, Garberville, California, 1976.

New England’s Ancient Mysteries, Robert Ellis Cahill, Old Saltbox Publishing House, Inc., 1993, Salem, Massachusetts.

No Stone Unturned, Louis A. Brennan, Random House, New York, New York, 1959.

Prehistoric Avebury, Aubrey Burl, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1979.

Riddles in History, Cyrus H. Gordon, Crown Publishers, New York, 1974.

Ruins of Great Ireland In New England, William B. Goodwin and Malcolm D. Pearson, Meador Publishing Company, Boston, Massachusetts, 1946.

Spain at the Dawn of History—Iberians, Phoenicians and Greeks, Richard J. Harrison, Random House, New York, 1987.

Viking and Indian Wars, Robert Ellis Cahill, Random House, New

York, 1987.

Cover

Archive

Editorial mission

Information for advertisers

Links

Directory

Calendar

Submission guidelines

Suggestions? Send us email