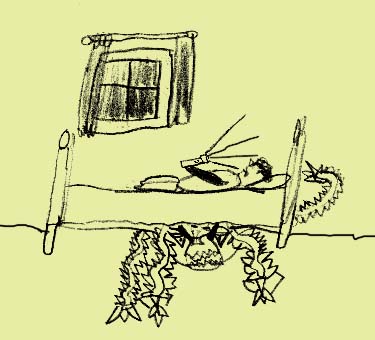

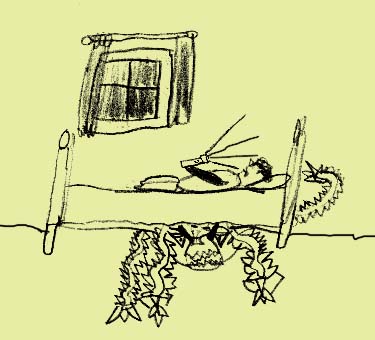

James thought he heard something rustle from underneath his bed

covers. He gripped his bat more tightly. He must not show fear. Monsters

fed on fear. That’s what his father told him.

James thought he heard something rustle from underneath his bed

covers. He gripped his bat more tightly. He must not show fear. Monsters

fed on fear. That’s what his father told him.

There was no movement from beneath the bed covers. “You’re trying my patience,” James said through his clenched teeth, saying the words just like his mother sometimes said them to him.

James’ room was dimly lit by a bright half moon and by a sickly yellow streetlight across the road from his window. “All right you monster,” James threatened, cautiously tapping the foot of the blankets with his yellow bat, “I gave you a chance, now you’re going to have to pay the consequences,” which was also something James’ mother sometimes said to James. “Are you ready, monster? Are you ready for the death light?”

James thought he heard something rustle from underneath his bed

covers. He gripped his bat more tightly. He must not show fear. Monsters

fed on fear. That’s what his father told him.

James thought he heard something rustle from underneath his bed

covers. He gripped his bat more tightly. He must not show fear. Monsters

fed on fear. That’s what his father told him.

“You’ll shrivel up and die if I use the light. You know you will. This is your very last chance to leave my bed and never come back.” James stood silent, holding his breath. He heard a car pass by on the street below and the television from downstairs in the living room. He heard nothing from his bed. “I don’t like being fooled with,” he said, imitating Miss Roe, his third grade teacher. “You’ve brought this on yourself.”

James slowly backed away from the bed toward the light switch on the wall near the door. He was sweating; a little, not much. He kept his body turned so that his chest was always facing the bed. He knew better than to turn his back on the monster. Waving his bat slowly from side to side in front of him with his right hand, James reached behind with his left, trying to find the light switch. The doorway never seemed so far away. One step back and another. James’ arm was getting tired from waving the bat in front of him. “Mustn’t let my guard down, mustn’t let my guard down,” James repeated to himself. His father had taught him about keeping his guard up while showing him how to box in the backyard.

James understood about letting your guard down and when his father had opened the arms in front of his face a little too widely, James had jabbed his clenched fist directly into his father’s upper lip. James was exultant for the briefest of seconds, then terrified. Before he could apologize, his father’s hand had lashed out and hit James in the exact same spot, knocking him over onto his back and bloodying his face. James’ tears mixed with snot and blood as he ran, sobbing, into the house, locking himself in the bathroom.

He could hear his mother yelling at his father as he came in the front door of the house and he could hear his father saying the words “accident,” “surprised,” and “sorry.” He heard “sorry” a lot. “James,” his father had spoken through the bathroom door, “unlock the door please. I’m sorry I hit you like that. You caught me off guard.”

James had sat on the closed toilet seat, his face still unwashed, tasting the blood from his split lip and thought, “I’ll never forgive him. I’m only a kid and he punched me in the face.” But then a small secret joy had grown in him and he repeated to himself, “I caught him off guard. I caught my father off guard.” James thought that adults were always on guard, always prepared for anything. He stayed locked in the bathroom until his father’s apologetic tone turned to anger and yelling. Later, he sat next to his father at the dinner table with a strange mixture of pride and apprehension over sharing the same fat lip.

James was not going to let this monster catch him with his guard down. He swung the yellow bat more vehemently, the indented grip tight in his small hand. His knuckles were white from clenching. “Where is that switch?” James thought as he stepped backward, his left hand finally finding the wall near the door frame. One last chance for the monster before James destroyed it with the light. “Okay monster,” James said secure with his hand on the light switch, “you can get out of my bed now or the light will shrivel you like an old tomato. You won’t be able to scare anyone then, nobody’s afraid of a tomato,” James thought that maybe he would be afraid of a tomato if someone, like Jay Krantz at school, put one down the back of his shirt and he didn’t know what it was. He waited, but there was no response from his bed. James worried that the monster was playing with him, waiting until the last minute to strike. “That’s it, monster, I’m counting to three and then I’m turning on the light and you’ll be destroyed. One,” James paused. Nothing. “Two,” he paused again, still nothing. Just as James was about to yell “three” with his eyes clenched tight, bat waving furiously just in case the monster chose that moment to attack, just as his hand started pushing the light switch upward, the door burst open and a giant hand flicked the light on, yanking two of James’ fingers in the process and inadvertently propelling James toward the wall. James screamed, and eyes still squeezed tight against the sight of the monster shriveling, lashed out with his bat, making violent contact with some part of the monster’s body and causing it to bellow in pain.

“Waauuggh!” yelled the monster.

“Aaaahhh!” screamed James as the bat was wrenched out of his hands. He heard it hit the wall near his bed.

“What the hell are you doing?” yelled his father.

“Dad?” asked James, allowing his eyes to open just a tiny bit. He saw his father kneeling down, rubbing one of his knees. “Did I get it?”

“You got me, James. Right in the knee.” James could see that his father was not so angry, but the other word his mother used to describe how James sometimes made her feel, “exasperated”. His father looked exasperated. “James,” his father said evenly, “what are you doing? It is ten-thirty at night and you are standing in the dark with a bat talking to yourself.”

James knew what he had been doing. Why did adults always have to tell you all over again what it was you were doing when, after all, you were there doing it. It seemed kind of silly, as if they couldn’t believe their eyes so they had to describe what they saw in words just to help them understand. The problem, James thought, was that the adults believed more in their words than what they actually saw.

“There was a monster in my bed,” James said.

His father looked at him. Then he looked over at the bed, the covers thrown over into a pile near the wall. “I see,” he said. But James knew he couldn’t.

Cover

Archive

Editorial mission

Information for advertisers

Links

Directory

Calendar

Submission guidelines

Suggestions? Send us email