Chiaroscuro: In Defense of Darkness

By Bonnie Hoag

People who call themselves energy-workers have many ways of effecting

change in the world, as they deem such change is necessary. One colleague

uses a technique she calls “pinking”. She waits on tables.

If one of her customers is rude or aggressive she imagines that person

surrounded with pink light.

When she first spoke to me of it I felt a visceral resistance.

I felt she was interfering in a process which could be allowed to play

out safely by another means. I’m not promoting rudeness nor condoning

it, but it seems to me in spiritual work that it is our responsibility

to allow and support processes rather than to interfere with them.

Many practitioners want to make everything okay right now! Interference

is, to my way of thinking, an unwise witchcraft.

Let me address this another way. Several years ago I was receiving

a Rubenfeld Synergy treatment from a gifted therapist. In an effort

to neatly finish up his work on me – in compliance with the clock

rather than the process – he began scooping “stuff”

away from my belly. I was alarmed by his presumption. Hey, whoa, wait

a minute! For me it was like theft. This is my belly and my stuff.

I wanted to take the time to move through it thoughtfully, not whisk

it away in a surgical strike.

Let me address this another way. Several years ago I was receiving

a Rubenfeld Synergy treatment from a gifted therapist. In an effort

to neatly finish up his work on me – in compliance with the clock

rather than the process – he began scooping “stuff”

away from my belly. I was alarmed by his presumption. Hey, whoa, wait

a minute! For me it was like theft. This is my belly and my stuff.

I wanted to take the time to move through it thoughtfully, not whisk

it away in a surgical strike.

Many of my ideas about “intuitive healing” sprang from

that experience. Rather than sweeping away emotion and dis-ease from

people, we can gently lead them, through guided visualizations, journeywork

and soul retrieval, allowing them to make their own discoveries and

rediscoveries, supporting them as they delve deep into their emotional

– their soulful – depths. Dive, or maybe for starters, just

stick a toe into the ancient waters.

My therapist was surprised by my choice. Perhaps I was his first

client who chose to keep what I had not yet spent time with, acknowledged

and released – more consciously.

Addressing the issue further, I have other friends who engage

in the shamanic practice of “extraction” which can remove

“unwanted” entities and other junk, both symbolic and real,

depending on one’s belief system. One friend whom I rely on to

drum and guide me in dreamtime journeys now allows me to address directly

what she might have simply extracted from me before she understood

my predilection.

My colleague who “pinks” people doesn’t describe

it as self-defense, but that is what I find when I track it to the

heart. Self-defense is a natural and healthy response to a dangerous

reality. We are easily provoked. There is much danger. Even so, nuclear

warheads seem to be an ironic self-defense given their ability to destroy

us all, wild ones included. Where is the self-defense in weapons of

mass destruction?

It’s obvious that “pinking” someone is a far cry

from storing or rattling nuclear warheads, but it is the essential

motivation which interests and concerns me. What if instead of intending

a specific effect on the other person, we imagine the same pink at

the edge of ourselves, so that all who come in contact with

us would be affected? This slight shift in intention and effect still

honors our sense of safety, but also our responsibility not to interfere.

It seems to me the changes need to be made within! We need to

“pink” ourselves – not others – or at least

certainly not without their permission.

This leads me to another bone of contention. I have with the

“light bearers”—what is wrong with darkness? Sure we

have associations with ignorance and evil, but are those not our own

fearful inventions? There’s nothing inherently hateful about darkness.

It can be a refuge, the quiet place where seeds begin to sprout, the

womb, a place of dreaming. I imagine us softening with each further

understanding and appreciation of darkness. Instead, what I witness

among my colleagues is a brandishing of light, as though they are “Star

War” heroes. I think our work calls for a deeper kind of courage,

without posing enemies.

Not long ago, in a sweat lodge for women, a thunderstorm came

upon us. This same friend who “pinks” revealed that she had

placed a protective layer of light around the little lodge to protect

us from the lightning. When she revealed to us what she had kindly

done on our behalf, I protested, “Please don’t do that for

me!” Her need to surround us with light revealed her fear, and

I did not feel protected by her fear. Rather than feeling safer, as

she does, by her action, I felt compromised, less safe.

Again it feels like interference rather than supportive allowing.

If, in that lodge, we were doing sacred work in non-ordinary reality

– which I choose to believe – why would we need this primitive

self-defense? What if her action, and perhaps more fundamentally, her

fear, was the attractive nuisance, with her imagining the strike, as

she did, entering the lodge along the trees and into the tangle of

roots beneath us. Instead, we could have imagined the darkness protecting

us—“under dark of night.”

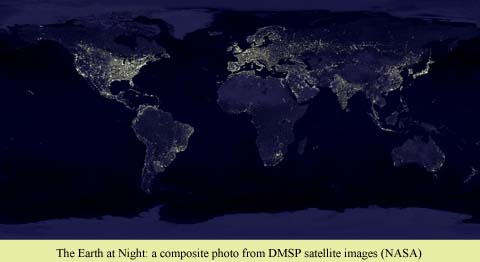

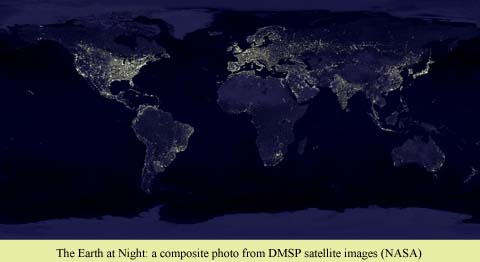

Imagine, now, with me, how our overall health could improve if

we could release our “addiction” to light. Imagine how the

land could rest again at night, without the creeping light of cities,

shopping malls, prisons. Imagine the possible implications of welcoming

the darkness, of dwelling in it, returning to a rhythm which allows

night, and darkness. I would feel safer in a world that does not sanctify

light above darkness. The production of electricity, our main defense

against the dark and fear, is costly in many ways. Imagine the desirable

consequences for our air, water and land if we did not fear the dark

but learned to work with it and to sleep and dream when the earth and

sky called us to do so.

We seek enlightenment. When will we also seek endarkenment? Darkness

is the dreamtime, whether at night cozy in our beds or when entering

the journey, the alpha state of what is called non-ordinary reality.

Darkness is what was feared in women, the very womb as replicated in

the tradition of the sweat lodge, and in the moon, coming and going

through its phases, dropping us sometimes into total darkness. In many

cultures the moon is symbolic of woman. Is it the darkness in woman

that has led to her oppression around the earth? Is it something so

primal in us as fearing the dark mystery, the potential of the womb?

Can our attention to light illuminate other oppressions, including

the connection between our fear of darkness and the oppression of dark-skinned

people around the world? In this short essay I leave us each to puzzle

it through.

When we experience another’s rudeness, thoughtlessness, or

condescension we can wither from it, rise to it with like demeanor,

or, returning to the stimulus which brought about my broad response,

we can “pink” the person. Or we can engage with them in the

moment, with the intention of changing us both. This technique may

be the most difficult and yet most revelatory because it insists that

we recognize our fear and be incited (insighted?) by it to choose compassion

over fear. That is the choice I’m practicing, though feebly I

admit. It feels like the most dangerous response until we recognize

the safety of compassion. Is compassion light? Is it darkness? From

where in us does it spring? Our hearts? Our bellies?

Rather than “throw light” at our problems, I invite

us to encapsulate them only as a last and temporary resort, to put

them on hold and engage instead with the fear in ourselves: shaping

those warheads into plowshares of compassion.

In the last year I remembered that fear and compassion cannot

simultaneously occupy me. When I am fearful, which is much of the time,

I am “outside”, threatened, keenly aware of my vulnerability.

When by choice I shift to compassion, my heart sighs relief. I see

my fear for what it is: a force with many dispositions and faces. Then

I feel the solace, the comfort of courage and compassion – for

my self and for the other, formerly obnoxious, human being. In that

state of grace we transcend our fear, and embrace our humanness. We

turn toward our fear, choosing to expose our vulnerability. We choose,

empathically, to bask not in the light this time but in the deep, safe

darkness.

With compassion, evil reveals its true self as fear. Yours, and

mine.

Bonnie Hoag is co-founder and director of Dionondehowa sanctuary

and School in Shushan, NY, DWS&S is non-profit and located open 175

acres bordering the Battenkill (“Dionondehowa,” before the

Dutch came). While the sanctuary serves as a refuge and recharge area,

the school is dedicated to nature studies and to the healing and expressive

arts, using them to engender social and environmental responsibility

in an atmosphere both contemplative and joyful. Dionondehowa translates

to “She opens the door for them” and may have referred to

the Eastern Door of the Iroquois Nation. For more information: (518)

854-7764 or at www.thegraphiczone.com/dionondehowa. “Chiaroscuro”

is an excerpt from the book Snake Medicine by Bonnie Hoag, available

by December 2001.

Cover

Archive

Editorial mission

Information for advertisers

Links

Directory

Calendar

Submission guidelines

Suggestions? Send us email

Let me address this another way. Several years ago I was receiving

a Rubenfeld Synergy treatment from a gifted therapist. In an effort

to neatly finish up his work on me – in compliance with the clock

rather than the process – he began scooping “stuff”

away from my belly. I was alarmed by his presumption. Hey, whoa, wait

a minute! For me it was like theft. This is my belly and my stuff.

I wanted to take the time to move through it thoughtfully, not whisk

it away in a surgical strike.

Let me address this another way. Several years ago I was receiving

a Rubenfeld Synergy treatment from a gifted therapist. In an effort

to neatly finish up his work on me – in compliance with the clock

rather than the process – he began scooping “stuff”

away from my belly. I was alarmed by his presumption. Hey, whoa, wait

a minute! For me it was like theft. This is my belly and my stuff.

I wanted to take the time to move through it thoughtfully, not whisk

it away in a surgical strike.