I trust a good deal to common fame, as we all must. If a man had good corn, or wood, or boards, or pigs to sell, or can make better chairs or knives, crucibles or church organs, than anybody else, you will find a well-beaten road to his house, though it be in the woods.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

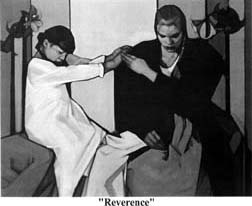

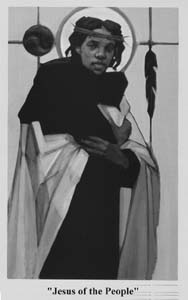

Emerson said nothing about good paintings of Jesus, but he might as well have. Janet McKenzie, a painter living in tiny Island Pond, VT, lives as proof of Emerson’s observation. Janet entered her painting Jesus of the People in The National Catholic Reporter’s Jesus 2000 competition, and won. Her painting of Jesus is a radical change from the familiar, standardized images. Since then, the reactions, invitations and requests for interviews have been pouring in from all over the globe. The spotlight can be hot and harsh, yet Janet seems as gracious and accepting of both the pleasant and unpleasant aspects of fame as the powerful, luminous figures that fill her canvases.

Janet: As I was waiting for your call, I was reflecting on a thought I have had continually, and that is, the simple gesture of watching the leaves come and go, and I felt every answer was right there, there was no more than that, and no more necessary. Everything is built into that—trust, and a life, a life span, birth, and death. It’s amazing—it all comes in a state of stillness. And that’s one of the things I love about here, my home in Island Pond. There was no rational reason to move to this particular place, we just took a chance, bought a house at an auction spur of the moment—we feel delivered.

Sue: How did you arrive at that spur of the moment decision?

We had been living in Albuquerque, Tom working for Intel. I have a very small cottage in Colchester. The job ran out, so we returned to Vermont to my little cottage. It’s seasonal, so we knew we were going to have to go somewhere else. My son was returning to Lyndon State College for his last year. We drove up with some of his belongings, and we said there’s an auction in this little town, let’s go up and see it, and it was over—we were too late. They were at that moment trying to sell the house, and nobody would buy it—so we did! We just did. It was our dog—who is very nervous, afraid of everything. He was instantly at home in this house, and we both looked at each other, and we looked at this place, it looked like a bomb had gone off in it—it was horrible—yet it was right! Opportunity comes, and you recognize it. You don’t always recognize it in the usual way, you know, well, I’ll go home and think about it and call you, you know…follow your heart—it’s there. So we did. That was five years ago.

Have you had moments of doubt, or has it been that once you answered the call or whatever, that things just have flowed…?

We have no regrets about having made this decision to take responsibility for this property, yet it has been difficult in many respects, too. It’s primarily because of the extreme isolation of the town, and we probably haven’t confronted that enough, and dealt with it.

What do both of you do in terms of working and being part of the larger world?

We have sort of a rhythm to the day. We get the day going, we organize things, we deal with obligations, for me, primarily ones that have come as a result of winning the competition. If there are too many, I can’t concentrate, so I take that to a level that’s manageable, then I focus on painting. As far as being part of the larger world, I never even realized that, partly out of need, a real sense of community takes place in a place like this. We have a neighbor that we care a great deal about, who, over the course of our time here, lost her husband. Our thinking now includes her. We have a very big regard for her well being and safety and comfort—she’s part of us, now. Even at times, my thoughts of leaving here, go to her. So, she brings a little tiny bit of the outside world to us through her own vision, and her past. I don’t invite the outside world in—I let it be in whatever form it comes to me, because I already have more than enough, in a sense.

Having come from New York 25 years ago, I am so relieved to no longer be around that enormous distraction. Just the distraction of going down the street, managing your eyes, avoiding getting yourself in trouble—that was so expensive, emotionally! I paid a big price, over time; it was habit, a way of living. There’s a lightness about being here, which is not true about other places that I have been.

It is almost as if places themselves take on characteristics of the people who have come before, and we who follow may think it is our stuff, but often we are reacting to what has happened there.

Yes! I lived in a house in Isle LaMotte, when I was with someone else, but the people we bought the house from were unhappy, and by the time we left, we had broken up. I honestly thought it had something to do with that house.

I think it is true of houses, towns, even whole regions. I think it’s true of paintings, too—or anything creative—the energy and intentions of the painter or the creator become part of the creation, and that affect people who come into contact with it. There’s vitality in a real painting put there by the painter that can’t be there in a reproduction. The consciousness that you bring to something that you are doing becomes a part of it, and that has got to affect the viewer, beyond the color and meaning of the image itself.

As you know, everything is interconnected. There’s a link everywhere. If I change just one mark in one of my paintings, it affects absolutely everything in the whole work. Nothing can be easily changed, that’s why it’s built with balance in mind.

Your paintings have this affect on me which is very much in the heart—a mixture of tears and compassion, of emotions rising up to be cleared out.

You know, sometimes I can look at my own work, and they affect me the same way. I have this sense of relief, I feel a sense of connection that I find, well, not an answer, but a similar reflection of what I am feeling that gives me a feeling of relief, which frees me to express my emotions, which could be tears.

People have been saying this about Jesus of the People. This painting is way beyond me. I mean, I do consider myself only the technician, that it came through me. But it is transcending, and I think it is the quality of transcendence that comes through some of my work, and particularly Jesus of the People. People are saying the strangest things— "the painting looks like my brother" when the brother is a 60-year-old white guy and, "Oh, that looks just like my mother!" You know, people are identifying, and I think maybe you resonate with, you recognize something in there, because I have no agenda, except to allow whatever is in the heart to come out. Someone once said to me "What’s your process—how do you work?" I get out of my own conscious way, as much as a person possibly can.

I think true Passion is life force, or Divine will, or qui, chi, prana, whatever—that wants to be expressed through us. Any suffering or any negativity associated with passion or emotion, is from getting in the way of it, and when we get out of the way of it, then amazing things come through. But it is not easy to get out of the way of it.

Oh, absolutely. It’s sometimes unachievable, and that’s a terrible feeling. For me, I think Passion is when we glimpse, however abstractly, the potential for success, whether it’s finding the right word, or, in my case, making the right decision, I know, however abstractly, it’s a glimpse. However, on this subject, its semantics, you know—words fail.

I rejected Christianity for years. It seemed so dogmatic and judgmental, focused so much on sin and guilt. But in my early 30’s, I thought, surely the religion I was born into has at its core as much truth as exotic eastern religions and philosophies. I looked at the more mystical aspects of Christianity, at what Jesus really taught, and I was so moved. Acceptance and forgiveness toward the learning process, toward ourselves and our mistakes, are at the core of Jesus’ teachings. It’s not to excuse atrocities, but to know that acting from passion is how we learn, and how we eventually integrate and transcend suffering, turn it into its higher form of compassion…

Yes, passion as the potential for success, for transcendence…Since I am now associated with this image, people want to know what religion I am, and when I say I have no religion, some of them are offended, incredulous. When I say I don’t feel I have to look for God or Jesus, I have a feeling that the essence of Jesus is inside me, with me!

If people expect an idealized Jesus who bestows answers, they are probably disappointed, but if they are open to Jesus as representing the inherent goodness or potential within us all, as well as the learning, then they see something else entirely. Whatever they’re feeling is reflected back to them.

This is exactly what I have been hearing—you know "he’s so angry, he’s smiling, he’s sad…" There’s not an aspect of the painting that hasn’t been totally confronted, ripped apart, or celebrated. I mean, everything!

It must be fascinating to see all that, to sit back as that goes on. Do you get a chuckle out of it, does it amaze you, does it just flow by?

Well, like I said, I feel like the painting is on its own path, it simply came through me. And I’m honored to have been given this responsibility. Several years ago I reached a level, a plateau in my work, and I put out there, I said, and I know I was talking to God, "Please, give me greater service. Use my talent for something greater." That was maybe three of four years ago, and it was shortly thereafter that I first started doing spiritual work. But to answer your question, it’s been frightening, from the most direct threats I’ve received—I became very frightened once, and angry, to laughing with my whole heart open to the world. But mostly I have been trying to see the work as other people see it, to share it and look at it from other people’s point of view.

That’s another form of passion, dispassion, which is a big component of spiritual paths.

You know, one of the hardest things about painting is knowing how to detach, when to call it done, and not keep picking at it. Do you ever look at Jesus of the People and think "Oh, I wish I had done that part differently?"

Yes, there are a couple of things that I do say to myself, and things I should have done differently.

But now it’s too late, because it is reproduced everywhere.

That is the perfection of it, though, because it needs that as well, and that I totally accept and celebrate, because we are never done, we’re never perfect, and neither is the painting.

I’m curious about the palette you choose for your paintings, and how you approach your painting.

I approach painting in a different way. I think like a sculptor. I’m not too interested in conveying a reality, primarily in back of the figure, because you can go way off on that. The palette—I simply cannot paint with browns and yellows and earth greens. I have a real aversion to those colors. It’s always been true, so I can’t work with them. I prefer very pure colors, a lot of ultramarine blues, a lot of pink, I do use a sea green, blue greens—they just resonate with me, so that’s what I use.

When you said you prayed to have your work be of service, that resonated with me, because when I was little, and people asked me that silly question of what you wanted to be when you grow up, what I really wanted to say was an artist, but I didn’t, because I didn’t think it was good enough. I had this idea there was one best thing I could do to be of service in the world, and I thought it had to be more human service related, directly addressing poverty or violence or something. A lot of people think of art as frivolous—look at how it’s cut from school budgets first thing. You know, "art is a frill, it is not basic to education, like math and science, it’s elitist—when people are out there starving and illiterate, how can you sit around and paint"—that kind of thing. I took those thoughts to heart.

It’s amazing how many people don’t feel okay about it. I have known many people who cannot confront the pain of painting, though art really is creative expression, which is painful, and when people think it’s a lark, they don’t know!

I think what you just said, that art is painful, is liberating. I have always felt that pain, but I don’t think I have ever really admitted that to myself. I don’t think most people do.

There is not a day, particularly when I’m really in rhythm, and the painting is really going well, it doesn’t matter—every day that I begin over again, the record plays in my head—the record of doubt, of anybody who’s ever tried to stop me, for whatever reason, that they had of their own—control issues, men, well-meaning friends—even my own mother, who was frightened to death of me leading such an insecure life—but I have learned that it is the mechanics of the mind. The mind is like a terrible child—it misbehaves, it stamps its feet, it will be heard above all else, and you simply have to manage the mind. Once you recognize it, it almost becomes mechanical. Now, I have some relatively simple techniques for confronting this. One is, I drown it out. I play gospel music, and it resonates so profoundly with my heart, and I play it so loudly, I can’t hear those tapes. It’s just a technique to confront the mind, which doesn’t want the discipline that is necessary to do this work. And unless a person does it, they don’t know—creative work is the hardest work.

I completely understand this. I went to art school after two years at a liberal arts college, and it was so, so difficult, and I kept thinking if this is my passion, why am I not happier, why isn’t it easier? I think we get lulled or fooled into thinking that "following your passion" means we will be completely happy, life will flow effortlessly, that sweat and discipline are part of an unfulfilled life, not a life of passion and fulfillment. You know, if it hurts or is hard, it must be wrong. And the other thing with art is it is not only painful and requiring of discipline, but it creates vulnerability.

Yes, on multiple levels.

And in that way it is like the whole spiritual journey, the learning through pain and passion to master the self, understand the self, to open up so much to the truth of who you are, that you can love it, and forgive it, and let go of all the tapes that say you’re bad, and you’re faulty, and you’re not achieving enough—

And THAT is passion.

I never really saw until now the link between creative expression and what the Christ, or the Buddha, or any great spiritual teacher was talking about, but there it is…

There it is. One aspect of the pain of creativity this brings to mind is when I graduated from high school, my mother told me there was no money for college, and I was always pretty much in a dream world, thinking of blue skies and things like that, so I woke up pretty fast, and wound up going to the Fashion Institute of Technology.

I got into their fashion illustration program, which at that point was considered elite, only 50 people out of those who applied got in, and that was halved after the first year—pretty ruthless. I hated every aspect of being there, but I continued, and at the end, I had this teacher. We all had to hang up our illustrations of women in their nice clothes and all, and she told me all of my drawings looked like holocaust survivors and I needed to make them more salable or I would be cut from the program.

Well, blessing of all blessings—I said no, I would not change them that way, and she passed me anyway, and then I quit. Something was in order—it was that I made a commitment to myself. After that, I was able to move forward in a state of grace. It set something in motion, and I still live by that. You need something like that to fall back on when the pain of creating becomes too great. It’s like sit ups—once you get to a certain point, it’s seamless, you have done the work to get there, and it is a high, a pure example of passion, what we are built to do, to truly express ourselves.

Jesus to me signifies this kind of transcendence over suffering.

Transcendence requires skill, discipline and confidence, because without those things, you may have the potential, but you can’t fulfill it. You have to master the medium you have chosen to work with, through discipline and transcending the pain, so the medium becomes an instrument for pure expression. It’s like getting the medium out of the way, too, not just yourself and your "tapes," or other people’s "tapes."

I have never asked for opinions on work in progress, never. I wanted it to come purely from me, without other’s opinions. In this way, I have found my own way, I found my answers from within. It has to come from within. I worked as a model while I was in art school, and it was an affirming self-reflection. But at some point I realized that I had a decision to make—was I the painter, or the model? Which side of the easel was I on? I found I couldn’t focus on my own expression. So I stopped modeling, so that I could paint, purely from within.

Janet McKenzie may be reached at jmckenzie2000@hotmail.com. Her work can be seen at two locations in Vermont:

Elaine Beckwith Gallery

Route 30/100

Jamaica, VT

1-802-874-7234

greatart@sover.net

Blue Heron Gallery

100 Dorset St.

South Burlington, VT

1-888-863-1866

blueheron@dellnet.com

Reproductions of her work may be acquired through:

Bridge Building Images, Inc.

P.O. Box 1048

Burlington, VT 05402-1048

1-802-864-8364

www.BridgeBuilding.com

In addition to reproductions of Janet McKenzie’s paintings, Bridge Building carries a varied collection of religious and spiritual images in the form of cards, plaques, posters, photos and other gifts.

Cover

Other issues

Editorial mission

Information for advertisers

Links

Directory

Calendar

Submission guidelines

Suggestions? Send us email