The Community Farm at Bennington College is entering its fifth season of organic vegetable production for a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. This is essentially a shareholder or cooperative venture between the farmer and people who want a secure, local supply of fresh produce. It works like this: an interested individual or household pays for a season of produce in the beginning of the summer and the farmer makes a promise to provide a rich assortment of the season’s bounty, the weather willing. The Community Farm is one of two dozen farms with such an arrangement in Vermont and, some say, about 2,000 in the US. A big advantage for organizing farm sales in this way is that there is income in the beginning of the season when farmers are usually accruing most of their debts.

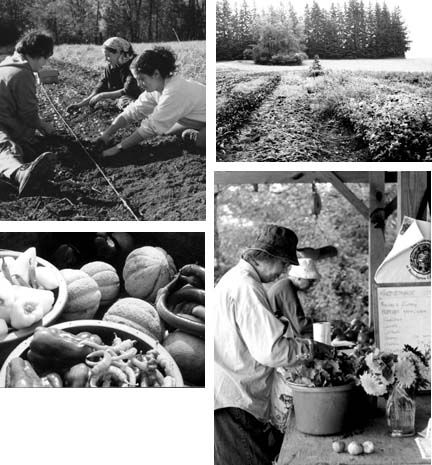

Bennington College is one of a few colleges engaged in a farm venture with its local community. Why would a college traditionally known for visual and performing arts want to get into farming? Six years ago, the College began a venture of utilizing its own land and educational heritage to offer its students and the community an opportunity to learn the value of responsible stewardship. It is also a tribute to the College’s efforts in WWII Victory Garden production of food for the college in times of need. Today’s student farm workers and researchers bring a zeal to The Community Farm that is unique and sustaining. They often work side by side with CSA members to cultivate the fields or prepare the day’s harvest for consumption. Emily Hunter, the one and only director of the farm so far, has found that the diversity of workers on the farm makes her job worthwhile. She returned to Vermont, the state where she grew up, after completing undergraduate and graduate programs in the Midwest. She was delighted to find that the new program needed a director and is now planning for the 2000 season. There is much license for creativity in the lay out of the fields and the selection of crops.

Sustainability, both economically and environmentally, is a critical component of the farm’s operations. Little of the five acres are ever left bare, either for soil erosion control in the winter months or for productivity’s sake in the summer. Soil fertility is carefully monitored and improved. Green manure and cover crops help improve soil structure and nutrient availability for plant uptake. Organic fertilizers are added with care. By the fourth season, Emily noticed some dramatic improvements in soil tilth, or the characteristics of soil that support abundant plant and soil life. Previously, the fields had been depraved of nutrient through the production of corn crops. In organic farming, workers are permanent sentries in finding new insects, both helpful and harmful. Insect monitoring allows the judicious use of biological methods of control and reveals indicators about the health/diversity of the cropping systems. Last but not least, sustainable and organic farmers grow a diversity of crops and mix them all together to keep insects and nutrient use in balance and to promote a healthy, mixed diet. It is important that people see first hand where their food is grown and under what conditions. Therefore, The Community Farm requires that most shareholders come to the farm and pick up their own produce. That way they can also have some autonomy in variety selection and they see the beauty of the fields.

The Community Farm at Bennington College actually has two major functions: the first is the CSA or shareholder program and the second is to provide fresh produce for the College Food Service. How could door to door delivery (often on foot) be fresher? The Food Service is willing to serve less conventional vegetables (especially if the students request them) and consumes a lot of standard items in the extensive salad bar. Students are an excellent source of feedback between the farm and the dining room. On the other end of things, a substantial amount of the food waste generated by the College is composted for return use on the farm. So far the first small piles have been used on fruit trees, raspberries and perennials.

To add a new product to the farm as well as a new life form, chickens

were added to the field rotations last year. Our small flock of laying

hens travels through the field in a movable pen or "chicken tractor". They

get new ground to forage on each day and eat weed seeds and insects and

we collect eggs. Perennial herb beds have been added to the number of annual

herbs grown on the farm and the raspberry patch is growing. To extend a

long-time interest in native grasses, Emily started a "grass nursery" of

a wide variety of grasses with the support of a National Wildlife Foundation

mini-grant. The number of species planted there will grow this year. The

Community Farm has many visitors from on and off campus and of all ages.

Those visits and the harvest days for the CSA program are very exciting

times. Visitors are encouraged (just get directions from the information

booth on campus) and there are still shares open for the 2000 season for

anyone in the greater community. New members are taken until mid-June.

Call Emily at (802)-440-4472.

Cover

Other issues

Editorial mission

Information for advertisers

Links

Directory

Calendar

Submission guidelines

Suggestions? Send us email